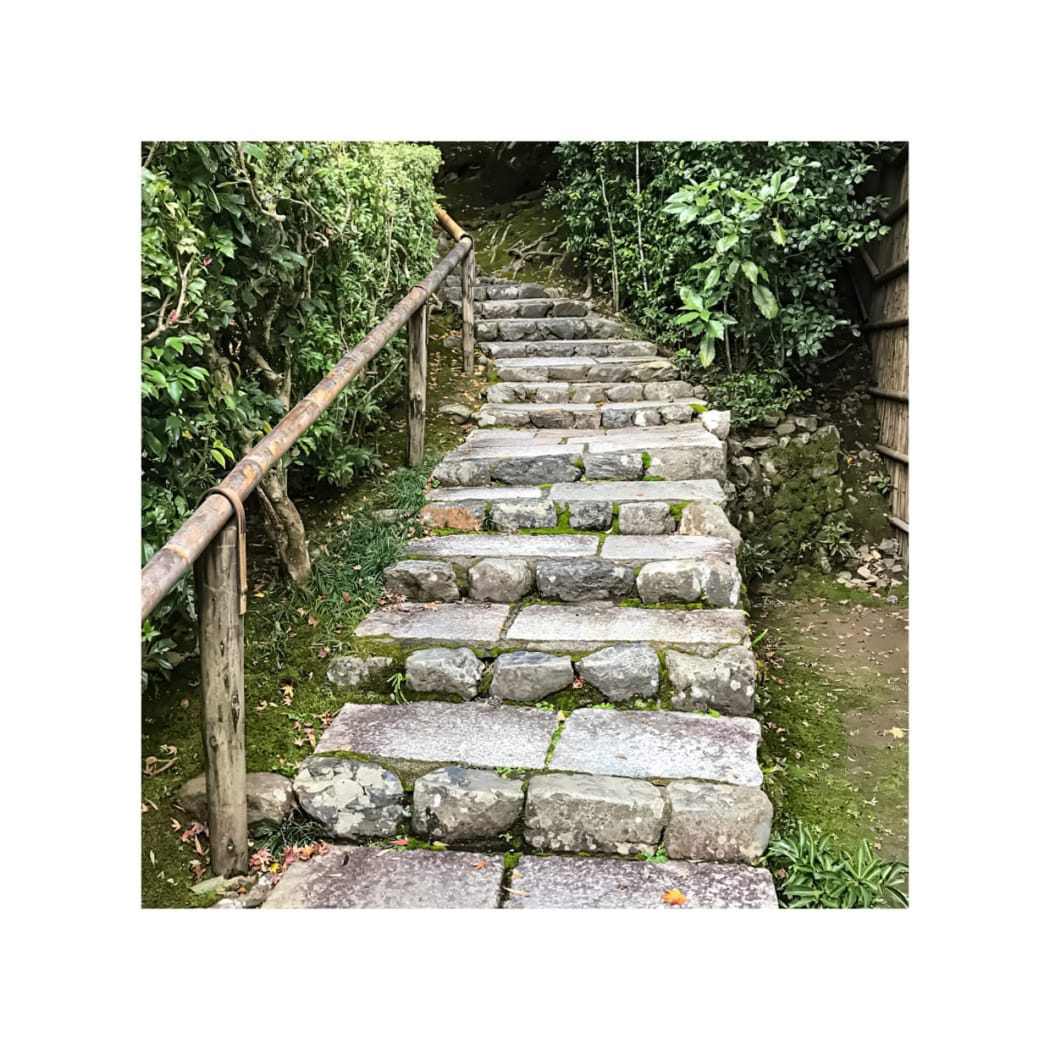

Pictured Above: Garden steps in Kyoto, Japan

A year or so ago, I encountered an essay on the Japanese garden by Saisei Muro (1889 – 1962), an excellent Japanese poet.

Muro wrote as follows:

Through Muro’s words, I received a jolt of recognition. Stones embody the profound refinement of the garden; the garden outlines the profound internal landscape of its steward’s mind. Gardens are as rich and mysterious as the layers of the human soul; much is hidden beneath the surface. As I sat with this realization, my mind recalled a dormant memory of the Rothko Chapel in Houston.

I first visited the Rothko Chapel while organizing an exhibition at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, during an idle 30 minutes between two final meetings. But once I truly understood where I was, I left. I would only come back once I had an entire day to sit, to see, and to give to the space all of the time and contemplation it demanded. A fleeting moment would have been a disgrace. On that day I walked out, but with time I would return.

Like the axis between two seemingly disparate points, Saisei Muro’s essay awakened my understanding of the connection between a masterpiece of American modernism and the tradition of Japanese Gardens. Both represented the concentration of honed intellect and power, buried under earth or paint until their effects reveal themselves in slow, deliberate moments. The essay exposed this essential quality shared by both, which only sharpened my understanding of each with greater clarity.

Nestled deep inside his works, Rothko buried an enormous power. Dark and cautious at first, the pieces may appear reserved. But with each successive breath you draw in their presence, the towering paintings begin to accept their viewer and little by little reveal the force of their tremendous beauty. Under layers of dark oil, you begin to see so many colors. As you enter deeper and deeper into the pieces, reflections of yourself are refracted in the rich surfaces. It took me two days, with a day of rest in between, to immerse myself in the works and the space. Still, I feel that I have so much more to take in.

It also reminded me of my own garden.

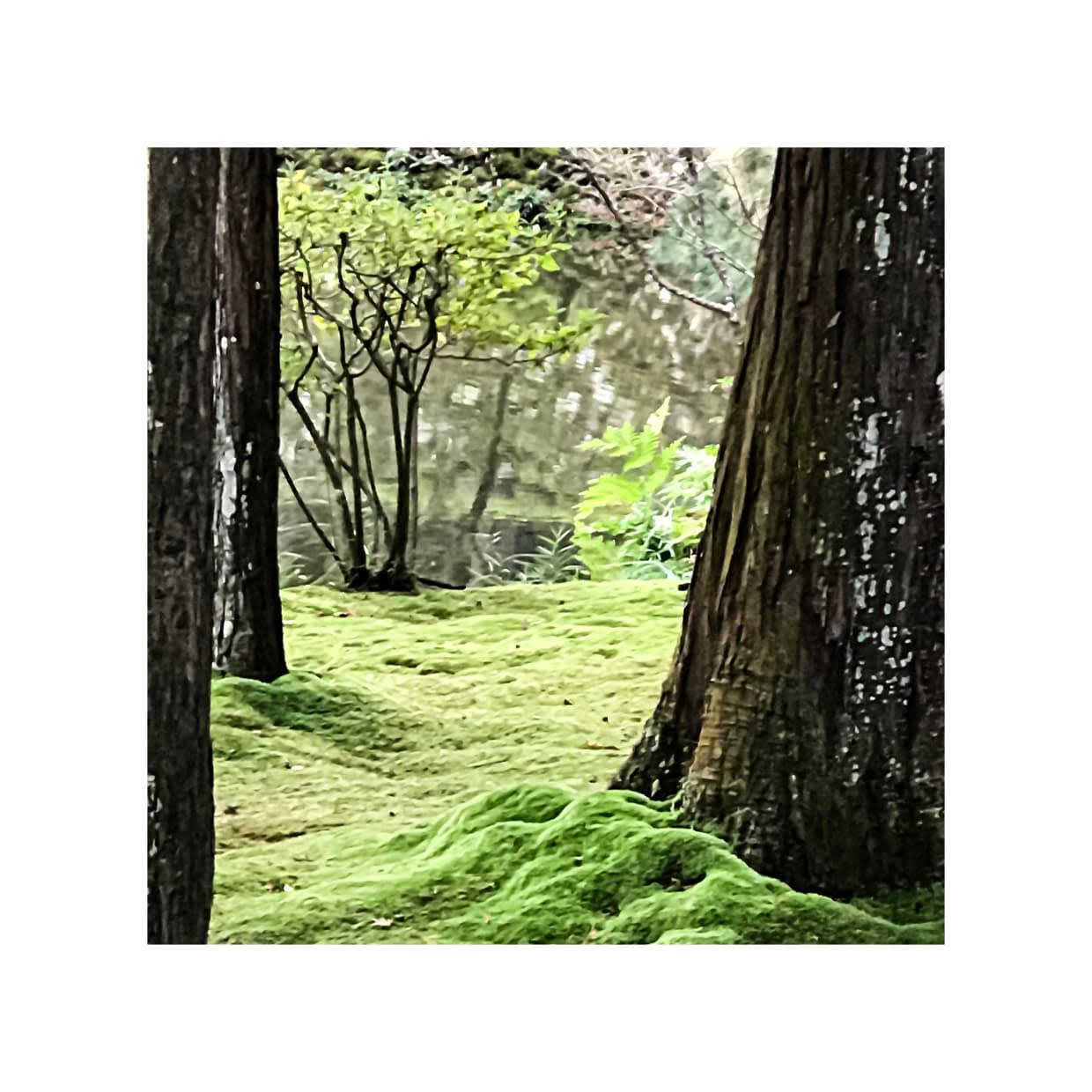

I was born and raised in a two-century old family home in Kyoto. The house had a beautiful Japanese garden with a small pond, a stone lantern, water basins, abundant moss, and a courtyard. From this garden, I learned about seasons; about the changing light cast at different times of day, about different plants or garden stones and many other shinbigan (aesthetic senses) by sitting on the engawa (covered porch) either with my grandfather or father. Hours would pass without the sound of a word between us. Sometimes he pointed to something, such as a ray of morning sun resting on a patch of moss shining shyly with dew. I held my breath with joy at the sight. Without words, my father and I exchanged a glance and smiled.

The garden lives, breathes, and feels with us. We grow up with it until we become responsible for its stewardship. Ten generations before me nurtured the garden of my early life. It felt times of joy and sadness, patiently watching over the comings and goings of our days for centuries. It absorbed our shinbigan (aesthetic senses) and constantly evolved with us, only to carry this buried intelligence to stewards of the next generation. If one looks upon a garden of great quality for long enough, they find that it reflects their own inner self.

The buried aesthetics of the Japanese garden reveal themselves perhaps even slower than in Rothko’s work; They cannot be taken in by a cursory glance. They are hidden beneath the familiar veneer of the garden, its stone lanterns, basins, moss, and plants. While these things may be beautiful on their own, it is the composition of the garden that speaks to the grace of its steward’s mind. In this spacing, centuries of Shinbigan are buried.

The highest forms of gardens are reflections of a deeply considered internal landscape. As with Rothko’s Chapel, we look to them, and see our own souls reflected back.

Pictured Above: Garden and pond at Saiho-ji Temple

Pictured Above: Tea House at Saiho-ji Temple